Recently I’ve been reflecting on a retail trade blog titled “Hyper-localization Is a Big Deal for Retail – and Even the Big Chains Are in on it.” This article went on to say that “the concept of hyper-localization is really a backlash against mass marketing.” Well, on the face of it, it would seem like anything that is hyper-local would be anti-chain. However, a deeper dive into this “new” hyper-local trend reveals a sophisticated marketing strategy designed to drive foot traffic to local retailers — be they local independents, or a local outpost of the ubiquitous chain store.

So how does this “new” marketing effort work? It’s important to analyze the fundamental strategy because in a world of struggling bricks and mortar tenants, finding the secret sauce to foot traffic is critical to the survival of retail streets and center everywhere.

The primary strategy of hyper-localization is to drive traffic from virtual shopping environments to bricks-and-mortar shopping environments. To achieve this goal, strategies aimed at combining

opportunities both to experience and to buy a product are employed because consumers have more of a connection and by extension will be more likely to purchase products they can see, touch and try. This correlation between experience and purchasing is the reason REI offers free classes, Williams Sonoma has cooking demonstrations, local bookstores have authors reading from their

latest works, and (brace yourself) Costco offers free samples.

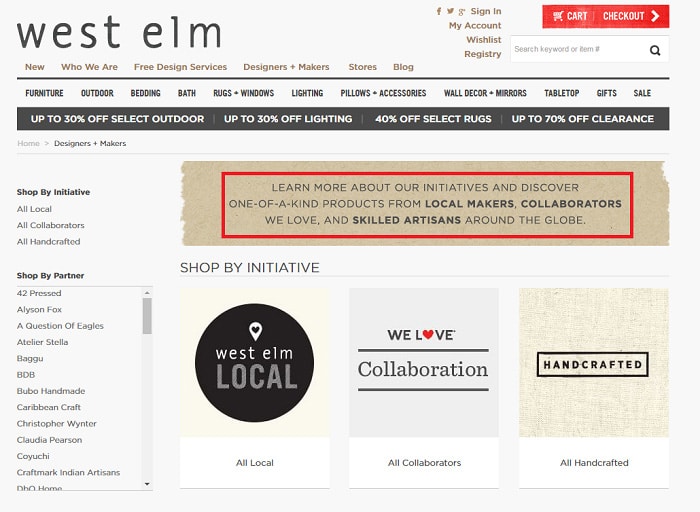

There are three important components to a hyper-local marketing strategy: Sourcing, service, and shopping. An example of sourcing would be a restaurant specializing in preparing food using local

ingredients, or a boutique featuring clothing by local designers. On the surface, local sourcing may make it look like hyper-local is about the local guy trying to survive in a chain-dominated world, but look closer: Check out the following screen shot where chain retailer Williams Sonoma-owned West Elm recently touted “initiatives and one-of-a-kind products from local makers….” It’s interesting to note that you can get 30%, 40%, even 70% off a whole bunch of stuff by clicking just above the feel-good, hyper-local pitch.

Service is key, and it’s tricky to execute consistently and well. Chain and non-chain stores alike need to differentiate themselves on service. Think about the difference in experience visiting an Apple Store as compared with Best Buy or Fry’s. One is far more service oriented than the others, and sales at Apple stores reflect that by having among the highest sales per square foot in the retail industry. Another obvious example of service is being able to order something on-line and then pick it up in at the local store. Again, this is a chain-store tactic to drive traffic from its on-line storefront to its bricks-and-mortar storefront where you might be inclined to pick up something else “while you’re at it.”

Finally, there is shopping. As mentioned above, converting an online visit to a bricks-and-mortar visit is a retailer priority. A store visit is “stickier” meaning you’re less likely to leave a store than move to a competitors web site. Cross shopping (buying other things at the same store) and an “upsale” to a different/better product are also more likely to happen in a store than online.

Executing hyper-retail marketing strategies is different for commodity as opposed to specialty retailers. Consumers patronize commodity retailers based on which offers the easiest or cheapest

solution to their need at a given moment. By way of contrast, consumers patronize specialty retailers based on what makes them feel good allocating discretionary dollars and “free time,” so

specialty retailers focus more on unique products and an appealing physical environment.